I used to think of Japan as an exotic, almost mythical place of emperors and shoguns, temples and Zen gardens, kimonos and tea ceremonies. It was a distant place where monks meditated in the mountains, strolling barefoot through deep snow, and Geisha women tottered over cobblestones on raised wooden sandals to work each evening. Back then, we said Japan was in the Orient, and the very word captured the mystique of the Far East. It was a place where exotic goods came from, but few ever went.

A closed society

Imperial Japan was ruled by emperors from 660 BC until the 10th century, when military samurai seized power and shoguns governed until the 19th century. When Buddhist monks began arriving from China in the 6th century, this insular island comprised territories of feuding warlords and samurai warriors. When the Silk Road reached this country in the 7th century, it wasn’t only goods that were exchanged with Europe and the Middle East—it was Western ideas and Christian beliefs.

Determined to preserve its religion and culture, Shogunate Japan closed itself off from the West in 1639 for 220 years. In 1867, the last feudal shogun resigned power to the Imperial Family, (Emperor Meiji was 14 at the time), and a country of castle towns raced to modernize. By the First World War, it was a world power.

After the Second World War, Japan rose again to become one of the largest, most advanced economies in the developed world, all the while remaining a masculine, monoculture and monolingual country. Japanese is the first spoken language of 98 per cent of the population. It has the world’s oldest population with 30 percent of its 126 million people over the age of 65. Despite an aging population and shrinking workforce, foreigners (mostly Asian) still make up only two per cent of the population.

Opening the kimono

I was a little apprehensive about spending 10 days in such a conformist society whose citizens spoke so little English. How would we navigate their punctual public transit network, switching with minutes to spare between bullet trains and commuter lines? Or order food from menus without pictures or English subtitles? Would we mind their good manners?

I wasn’t concerned for our safety. I knew that Japan, like Singapore, was one of the safest (and cleanest) countries in the world. Singapore, however, is a strictly-governed melting pot of cultures and religions. Japan is a very homogeneous, orderly, society that largely follows the ancient faiths of Shintoism and Buddhism. The two Asian religions co-exist because Shintoism teaches harmonious ways of living, while Buddhism prepares one for the afterlife.

To experience both traditional and modern Japan, we engaged a tour company and personal guides for Tokyo and Kyoto. The women took us further inside this once-closed society, revealing the ever-present beauty of this refined culture and its gracious people.

We arrived in Tokyo in January, so there were no cherry blossoms or crowds. Still, this megacity of 36 million seemed busy, but how could I, a blonde Canadian, tell a visitor from a resident? Most of their tourists – 20 million last year – come from East Asia.

Kyoto was a more manageable city of 1.3 million, and we walked across the Kamo River to the famous geisha district in Gion in hopes of seeing a geisha woman going to work in the evening. There are only 250 traditional geishas left in Japan. We were lucky enough to see two white-faced, kimono-clad geisha apprentices (maikos) leaving their mother house, and later a graceful geisha woman as she slips into a cab.

Our tour company provided a roving itinerary that took us from Tokyo to the west coast to sleep at a traditional ryokan (inn) and bathe in a private 42C onsen (hot springs). We cycled around one of the art islands near Takamatsu, paused at ground zero of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima, visited the feudal Osaka Castle, (where James Clavell’s novel Shogun was set in the 16th century), and saw the beautiful white Himeji Castle, a fortress which survived 410 years of fire, war and earthquakes. In Kyoto, we learned how to interpret a temple’s dry Zen rock garden and how a landscape gardener designs a strolling pond garden for the villa of a Shogun (1397), to reveal aesthetically pleasing views around each turn on the path.

I sit with our guide in our socks on the wooden steps of the Zen Buddhist temple while my husband takes photos of the racked rock garden from different angles. In this life, she is saying, everyone strives to be a better person. She recites a tale about a monk who passes all of Buddha’s grueling tests but still could not attain Enlightenment. Younger monks asked if he was disappointed. Not at all, he replied. Perfection, she explains with a modest smile, cannot be achieved in our lifetime: “The best we can hope to achieve in this life is 98 per cent.”

A friend forwarned me that food wouldn’t taste as good after Japan, and it’s true.

Everyday Haute Cuisine

A friend forewarned me that food wouldn’t taste as good after Japan, and it’s true. I read Osaka was Japan’s food mecca, but I was impressed by the quality of ingredients, skilled preparation and detailed presentation of dishes everywhere, be it a high-end department store restaurant in Tokyo and Kyoto, or packaged food from basement markets, or a narrow counter on a side-street, or a breakfast buffet at the hotel.

We savoured the traditional and classic dishes wherever we could. We had steak for lunch in Kobe, shabu shabu dinner in Himeji, ramen noodles in Kyoto, Yakitori tapas and sake in Tokyo, and a Kaiseki 10-course Matsuba crab dinner at a traditional Japanese ryokan (inn) in Kinosaki, a hot springs village dating back to the 1300s.

I knew that eating a diversity of foods helps feed the gut microbiome and keeps you healthy, so we were happy to discover the Japanese eat a variety of smaller portions with each meal. Instead of a North American dinner of broccoli, meat and potatoes, a typical meal would start with a cup of green tea and miso soup, several small servings of fresh and fermented vegetables, thin slices of meat or fish, and a little side bowl of rice and bite-sized pieces of fruit to finish.

Our city guides explain that Japanese socialize outside the home because homes are too small for entertaining. It’s very common for young people to gather at Karaoke bars and adults to meet at a restaurant and finish the evening at a wine bar. Over our meals together, we learn how to order Sake rice wine (its not like ordering wine), and the finer ways of handling chopsticks during a meal and sipping tea with both hands.

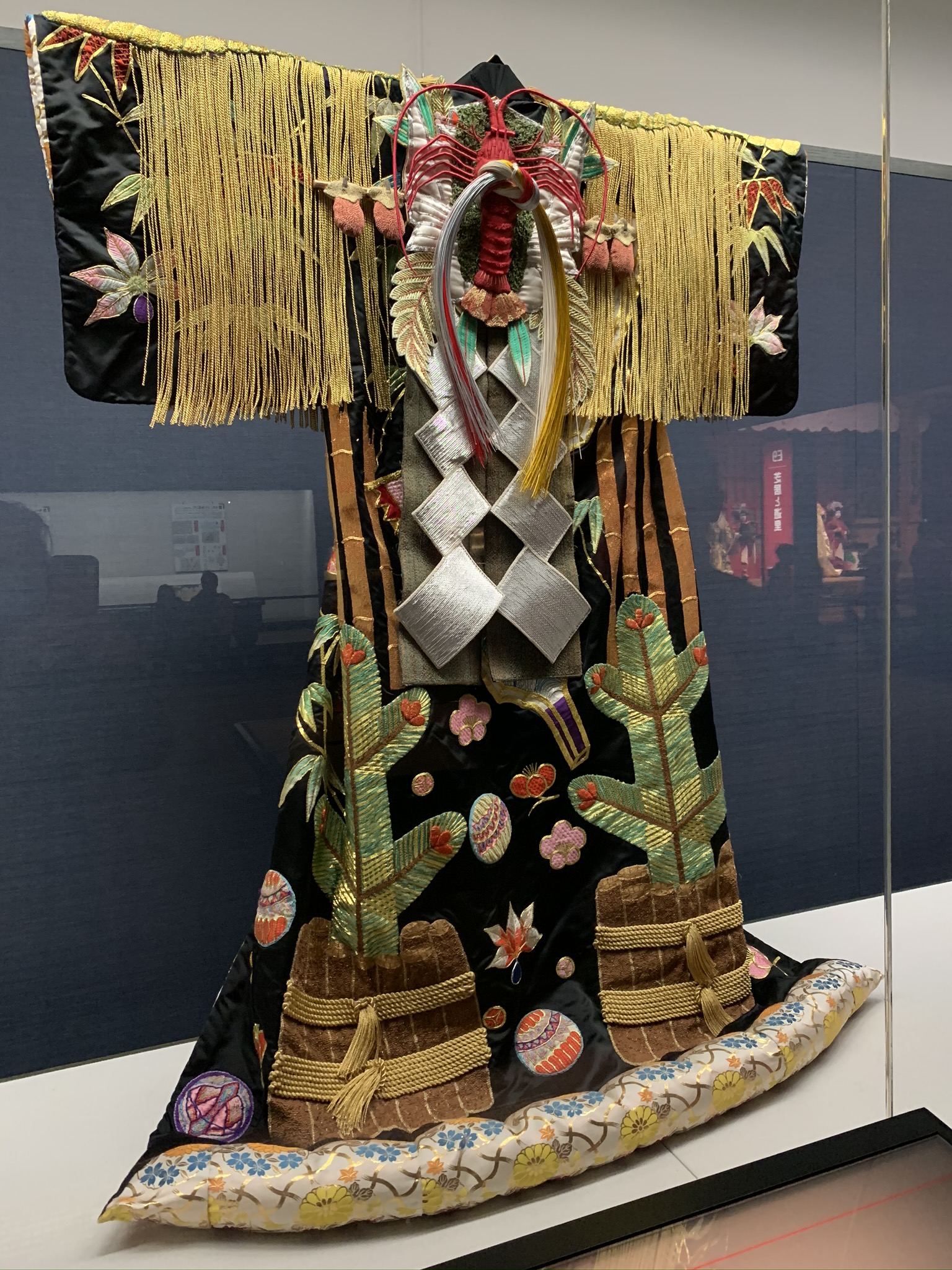

Cultivated beauty

From ancient calligraphy and elaborate tea ceremonies, to stunning Shogun castles and elegant geisha ladies, from intricate courtesan kimonos to simple flower arrangements, this once-closed society has been living and breathing beauty for centuries.

Perhaps it’s the lack of personal space that promotes this minimalist style and teaches one to possess only that which gives pleasure to hold and behold. Or maybe it’s their intrinsic eye for beauty. Might living in overcrowded cities contribute to the country’s cleanliness, efficiency and courteous citizens? Whatever the reasons, I now understand and appreciate the calmness they’ve cultivated in the space between things.

Standing over my emptied suitcase, I slowly gaze around at our downsized home, and I ask: why have I still so much stuff?

Well written word traveller. Fabulous country for skiing too

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is. The country is so long you could probably go to the beach in the south and ski in the north.

LikeLike

Sounds like an awesome trip.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was such an amazing cultural experience and I took away several ways of life.

LikeLike