Meeting our Flanders Battlefield Tour Guide

We are standing on a cobbled road in Ypres, Belgium, a medieval town in West Flanders that was flattened by 4.8 million shells in the First World War. We are waiting, a century later, for our guide. My husband and I booked a private tour to follow in the footsteps of my Canadian grandfather, who fought at Vimy in April 1917.

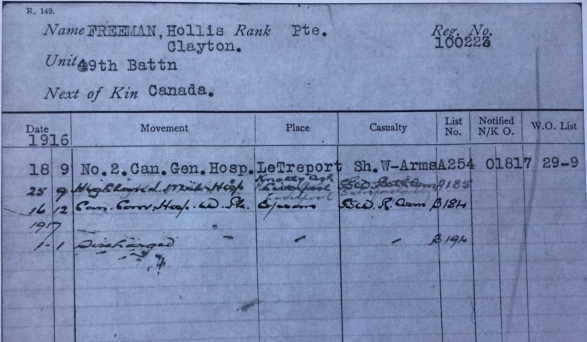

I had sent our guide my grandfather’s name and regiment number to research his whereabouts on the Western Front. I learned viewing Canada’s Personnel Records from WWI that my grandfather, Private Hollis C. Freeman, Reg. No. 100223, served until Armistice with the 49th Battalion, as part of the 7th Infantry Brigade in Reserve, 3rd Division of the Canadian Expeditionary Forces (CEF).

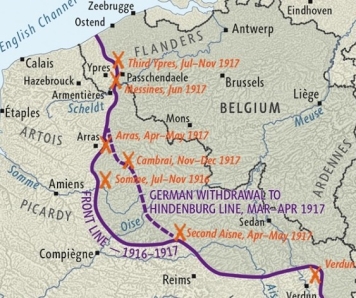

I was excited to be here, on the same soil as soldiers fighting for the British Empire. After greeting our Belgium tour guide, we are stunned by his next words: “Your grandfather never fought at Vimy.” He reaches inside the car for his folder of research and maps. “He was wounded in September 1916 at Courcelette, in the Battle of the Somme, and sent to a hospital in England. That’s probably what saved his life.”

We hop into his vehicle on this warm and sunny August day and drive south into France, where the front line action was in the fall of 1916. The Somme village of Courcelette is about an hour and a half away, so we have time to learn about the Battle of the Somme.

The Somme Offensive was three major Allied assaults between July 1 and Nov. 18, 1916. It was the largest battle on the Western Front, resulting in over a million casualties (missing, wounded or killed) to Allied and German troops in four months. WWI was fought in the trenches, and soldiers on the front lines were often fighting meters apart.

Traffic is light this Saturday morning, making it easy for us to zip through the dizzying number of roundabouts we encounter visiting Canadian memorials, museums, and Commonwealth cemeteries. The repeating scenery is one of rolling fields of corn, wheat, sugar beets, and potatoes. It’s hard to imagine this quiet countryside was a blistered ‘moonscape’ 100 years ago.

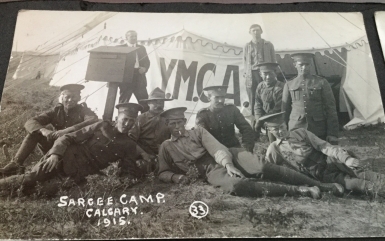

Private Freeman was 26 when he enlisted in Edmonton on July 1, 1915. He was transferred to the Sarcee training camp in Calgary but must have received a pass to return to Edmonton that Christmas because his marriage certificate is dated December  29, 1915. Service records show he left Calgary the following April and sailed in May from Halifax to England for training. A month later, he was sent to France to join the 49th Battalion, under the command of Edmonton’s Lieut. Col W.A. Griesbach.

29, 1915. Service records show he left Calgary the following April and sailed in May from Halifax to England for training. A month later, he was sent to France to join the 49th Battalion, under the command of Edmonton’s Lieut. Col W.A. Griesbach.

The Battle of the Somme

In mid-September, the 49th Battalion arrived in Courcelette to reinforce the Allies in their second major assault. “It was a bloodbath on the Somme,” says our Belgium guide. The British had suffered nearly 60,000 casualties on the first day of battle. The Canadians lost 8,000 men out of 24,094 casualties in two months.

My grandfather’s reserve infantry unit attacked September 16, wrote Lieut. Col Griesbach in his daily war diary: “Enemy shelling was heavy for two days causing numerous casualties.” The ground over which the battalion moved, he continued, was “absolutely churned up with heavy shell-holes. Not a square foot of ground was

undisturbed; the debris of a battlefield still remained…. The air was filled with smoke and darkness was coming on.” It was the first time the British used tanks, and my grandfather would no doubt have seen the six assigned to his battalion.

On Sept 18, under heavy artillery fire and wet skies, Pte Freeman was hit by exploding shrapnel in both arms. He was admitted Sept. 20 to No. 2 Canadian General Hospital in Le Tréport, Normandy. According to a Vancouver nurse stationed at Le Tréport in 1917, many wounded soldiers had been hit by machine gun fire or flying shrapnel. “Very few have one hole,” Nursing Sister Beatrice Kilbourne wrote in her diary. “More often we find six to 40 in one boy.”

Pte Freeman was shipped a few days later to Highfield Military Hospital in Liverpool, Eng. and discharged 81 days later. He spent the next three months at the Canadian Division Convalescent Hospital Woodcote Park in Surrey, Eng.

We head north to Vimy. Even though my grandfather did not make it here, I must follow his battalion. I am awed by the sheer number of military cemeteries we pass, and the row upon row upon row of identical white headstones.  These cemeteries, which are maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, are immaculate. Neatly manicured grass outlines unblemished, white headstones. Some have names, dates, regiments and trimmed rose bushes, while others simply say Known Unto God. All graves, identified or unidentified, are treated equally in death, says our local guide.

These cemeteries, which are maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, are immaculate. Neatly manicured grass outlines unblemished, white headstones. Some have names, dates, regiments and trimmed rose bushes, while others simply say Known Unto God. All graves, identified or unidentified, are treated equally in death, says our local guide.

Visiting Vimy

From the backseat, I glimpse the Vimy Memorial in the distance. This 28-meter-high monument dominates the seven-km ridge, its white twin pylons jutting into the overcast sky. Our guide wants us to approach the limestone monument from the front to fully appreciate its stark beauty and grandeur.

He appreciates the detail given to the design of Canada’s war monuments and memorials. He points out the leafy maple trees we are walking under, and over there, at the base of the twin Canadian and French flagpoles at the park entrance, are carved beavers.

The few visitors on the monument disappear as we draw near. “There’s no one here,” murmurs our guide. “It’s very rare to see this monument, never mind take

a picture of you on it, without anyone else standing nearby,” We three are the only living souls on this grassy escarpment that accommodated 25,000 visitors last summer.

Ypres was rebuilt to its prewar likeness in a Flemish medieval and renaissance style. But our guide says the city still lives with the devastation of The Great War. Beneath the regrown grass and fields and trees lie the remains of tunnels, trenches, buried bombshell fragments, unexploded war armaments, mine crater holes, and humans. “We’re still taking burials,” he says, adding they are burying four Canadians the week after we leave. We drive by a large greenish tinged shell lying by the side of the road. “This shell was dug up in the last couple of days and will be picked up and detonated.”

My grandfather was a carpenter from Edmonton when he volunteered. He had helped to build the High Level Bridge and the Royal Alexandra Hospital. His attestation papers gave the service term of one year, ‘or for the duration of the war now existing between Great Britain and Germany.’ I’m sure he never imagined, like most of the 630,000 enlisted young Canadian men and women, that he, along with 425,000 overseas soldiers, might still be engaged four years later in the largest, most destructive war in history.

On Nov. 2, 1917, Pte Freeman rejoined the 49th battalion at the Canadian Corps Reinforcement Camp in France. He was with the 7th Infantry Brigade when it captured Mons in the early morning hours of Nov.11, 1918. The following May, he sailed from Liverpool to Halifax and was discharged June 5, 1919. One in three Albertans did not return.

Each November, we honour the 61,000 Canadians who were buried where they fell on the Western Front, but this year, I will also remember the hundreds of thousands of other heroes, everyday Canadians, who served and came home. Hollis Freeman was 30 when he came home to his wife and a three-year-old daughter named Holly. He never spoke of the war again.

What an amazing walk through history you have followed. Thanks for taking me along! Mary Anne

LikeLike

Great to hear from you and thanks for following. We are in Thailand now posting on FB

LikeLike